When Eze Graduates from School: A Myopic Generation

The fathers have eaten sour grapes and the children’s teeth are set on edge – Ezekiel 18: 2.

The Generation of Hope, trailblazers chronicled in early tomes of Nigerian literature including, Eze goes to School, The Porter’s Wheel, and to some extent, Things Fall Apart, were expected and equipped to bring their communities into the modern age. They failed. Like Eze, communities fed and clothed these avatars; sent them to school, provided healthcare, housing, and transportation (some abroad), but got little in return for their efforts. With every grade passed, exam scaled, and graduation attained, the communities celebrated in expectation of a boon but got little in return for their investment.

To be sure, how many of these community-trained Ezes, built and passed on to their next generation corporations, schools, even the crusades they started?

As evident in these literature, their communities placed great hope in them to know the truth a la Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Unfortunately, while the Hope generation fought and won the battle for intellectual prowess, they lost the war for an independent nation. In truth, the trailblazers did not set out to fail, but they got derailed and turned their sights in other directions.

Why?

The smell of the village: The book didn’t continue post-graduation, but Eze probably returned from his overseas study to settle in Lagos (the story is common enough). He’d visit his village at Christmas or upon the death of his mother or uncle should he feel generous. Also, if generous, he’d take on the training of one cousin or thirty-five, but from his home-base in Lagos. Essentially, his ties to the village grew thinner each passing year. If his name was Kola, upon his return from abroad, he’d realize that his village was the headquarters of all the witches in Nigeria. Hence, he’d not only stay away, he’ll ensure they didn’t know where he lived. And if he was Bala, he’d return to the nearest city, find himself a lucrative government post, marry several wives, and begin his dynasty. He’d feed his people during Ramadan but would neither educate nor make any effort to develop the village. Given Eze and his cronies loath the smell of the village, they pass on their disdain to their children who now loath the smell of the nation and thus, live abroad.

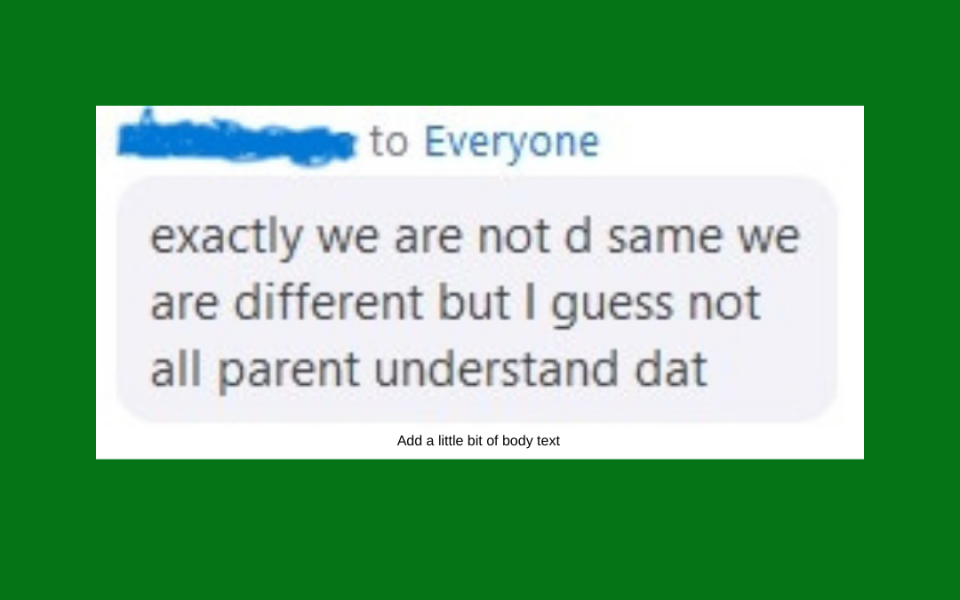

Lack of a Vision: A piece circulating on WhatsApp about Nigerian parenting states in summary, “Parents of the 1950s who were farmers, traders, and fishermen produced children who became lawyers, doctors, and engineers who then produced thugs, area boys, and kidnappers. Things that make you go, “hmm,” right? As a nation, we lack a national vision. Worse, communities which make up this nation, lack communal visions. Forget politicians, what do Ekiti kete want for themselves? Schools, housing options, hospitals, good roads, security, the usual suspects? Are these goals clearly defined anywhere? Is there a roadmap? What do they intend to hand off to the next generation?

Spoiled by Easy Pickings: The trailblazers were perhaps Nigeria’s first Entitlement Generation. They were fed, shod, schooled, and feted. Upon graduation, they chose from an array of jobs which offered company houses, cars, servants, healthcare, and food allowance. And the economy was sound. Until it became unsound; by which time, they were too spoiled to gird their loins to work harder. Instead, they figured, if their parents catered for their needs, so should their children and so began borrowing from tomorrow to feed their tremendous appetites.

Myopia: The oil boom decimated Nigeria’s intellectual prowess. With easy money flowing from oil, leaders thought it too arduous to pursue manufacturing, mining, and industry. For sure, agriculture would be a step backward. They assumed the oil would flow forever and proceeded to put all their eggs in that greasy basket.

Over-reliance on Governance as the Catalyst for Progress: Since the most educated were initially involved in the political battle for Nigeria’s liberation from colonialism, the nation looked to the government to lead it into modernity. And it delivered, particularly in the Western Region where it provided free education, healthcare, and other amenities. Unfortunately, power changed hands from visionary leaders to self-aggrandizing illiterates. Yet, the nation continues to look to the government to champion growth.

Lack of a maintenance culture: Once upon a time, the express roads were pliable. Then they became pothole ridden, pathways to hell. What happened? No maintenance. This story is repeated in every Nigerian institution, industry, infrastructure, amenity, etc. We start with great fanfare but don’t commit to upkeep or maintenance and soon, the story is told of glory days.

In fairness, the Ezes did face critical challenges including military coups, the Biafran war, and inter-ethnic clashes which destabilized progress made in specific areas. Unfortunately, they responded to these crises in self-serving ways that continue to hurt the nation today. Indeed, the fathers ate and continue to eat sour grapes and the children’s teeth are set on edge.

References

Eze Goes to School by Onuora Nzekwu and Micheal Crowder

The Porter’s Wheel by Chukwuemeka Ike

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe